More, better trains: lessons from the Tsukuba Express

London's commuter rail networks could learn a lot from Japan

Community notes:

A Greater Londoner wrote to us this week about a development in their local area, the Glassmill project in Battersea. You can find out more and support it here.

Are you passionate about London’s nightlife? City Hall is hiring for a Policy Officer to work on the 24 Hour London Programme, more info here. The deadline is tomorrow (Monday).

The Olympic Games opening ceremony in Paris may have had many of you nostalgic for the same stage of the London 2012 Olympic Games, those of you with a spare four hours can watch the whole opening ceremony here.

Written by Matthew Bornholt for the Greater London Project.

London’s train networks are world-leading, but they also struggle to cope with current demand. For London to grow and become less reliant on cars, we need railways which are an order of magnitude more effective and reliable.

Japan, another rich and densely populated island, offers one of the best models. East Japan Railway Company (JR East) alone has more daily passengers than the whole of Britain, but is only responsible for a quarter of Japan’s total ridership, and a third of Tokyo’s daily riders! British public transport can learn a lot from a system which has built that much more capacity.

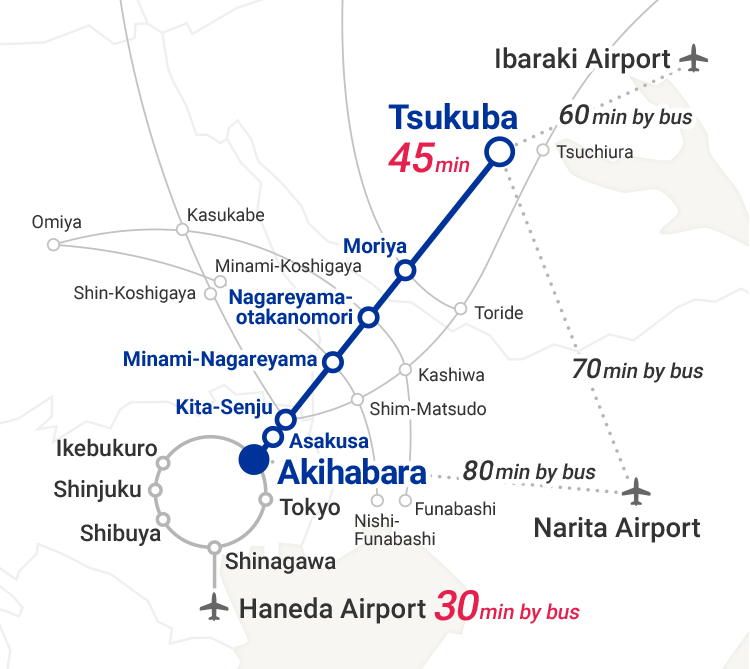

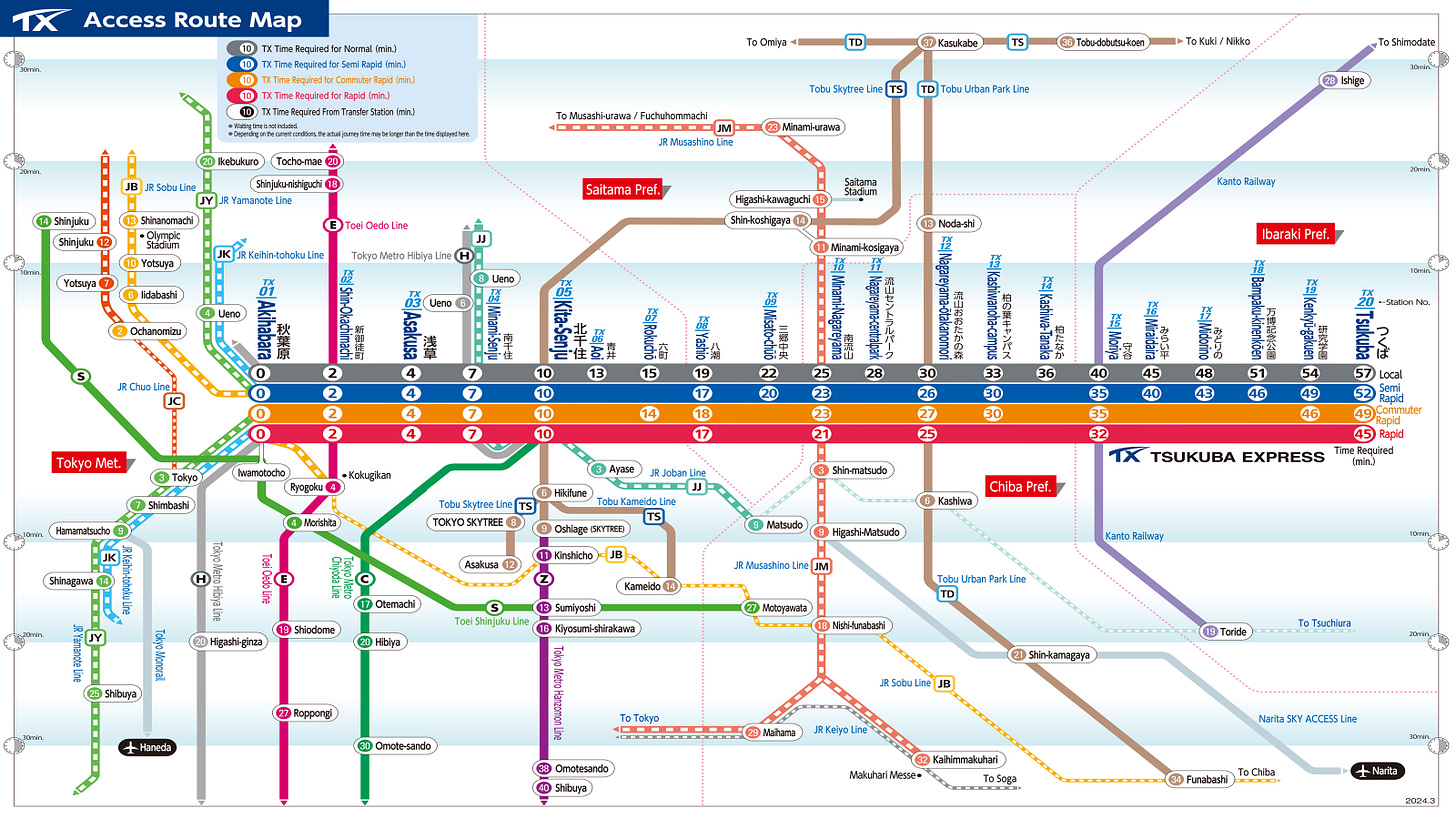

The Tsukuba Express (TX) was opened in 2005 and stretches 58 kilometres south from the New Town of “Tsukuba Science City” to Tokyo’s famous Akihabara district. The six-car trains make the journey in 45 minutes for express services and 57 minutes for stopping services, moving around 390,000 people per day before the pandemic. For comparison, Thameslink, with all its branches and 12-car trains, moves about 250,000. Supported by the line's service, new suburbs like Moriya or Nagareyama-Otakanamori are among the few in Japan with high population growth.

How does it manage this? The Tsukuba Express demonstrates Japanese rail operations philosophy, which emphases frequency and reliability over interlining, the practice of running trains across different lines to serve multiple destinations. Those connections are of course valuable, but they often create cascading delays across those different rail lines (Figure 3 shows this dilemma). In Japan the standard preference is towards less interlining and more focus on reliability and frequency.

The TX exemplifies this. It is completely separate from the rest of the network, which means its aggressive timetable is solely about its own operations. When Japanese railways interline, it's a strategic choice: they trade away frequency to preserve reliability. British Railways utterly sacrificed reliability and frequency for complex service patterns to give passengers different options. The exception to this rule is the London Underground, the best network in the country.

And then there are the stations. The Tsukuba Express’s two underground terminals only have two platforms each. The extra space for express passing services and timetable padding is created with three strategically placed passing loops at Yashio, Nagareyama-otakanomori and Moriya. This allows more than a third of all services to be an express route of some kind, and the TX has three different express routes for passengers looking to get to major destinations more quickly (see Figure 4).

How could London learn from TX? We already have a great starting point. The Northern City line between Moorgate and Finsbury Park connects through its own track to the separate Hertford loop all the way to Stevenage. It even has two legacy passing loops/turnbacks at Hertford North and Gordon Hill. Yet we barely use it, with some 4-7 trains per hour compared to the 11-24 of the Tsukuba Express. And no expresses.

How could we achieve the same level of service that TX does? As a priority, we should stop running trains from Moorgate to Welwyn Garden City via the East Coast Mainline (which run under the Great Northern brand). These trains currently interact with a variety of services on the congested East Coast Mainline, running as far as Leeds, Newcastle, and Edinburgh, which often makes the Moorgate service unreliable and delayed, for the small benefit of just two trains per hour. We should also add more platforms at Stevenage, since there is currently only one for Hertford Loop services – platforms which could be built over the Stevenage West Exit car park.

Then, to avoid overloading the Victoria line even more, connections to the less crowded Piccadilly line can be provided by rebuilding Arsenal and Bowes Park stations as interchanges with connecting pathways. They are also both good locations to add extra passing loops so more express services can run along the line. Using the Moorgate-Hertford-Loop-Stevenage line more efficiently also offers the chance to reduce the cost of Crossrail 2, since its proposed New Southgate branch could be made redundant.

In order to manage this we should follow the TX another way. Because most of this line is outside the GLA, we should avoid folding it all into TfL, which would create a democratic deficit for commuters from outside Greater London. Instead, like the TX, we should set up a separate operator jointly owned by London via TfL, Hertfordshire and the national government. Its modest immediate infrastructure costs could be financed independently, with construction costs funded by debt, to paid developer contributions and ticket sales. As the upfront infrastructure costs are modest, it should be financially viable to increase capacity and get to around 20 trains per hour between Moorgate and Stevenage, massively increasing the number of passengers who can commute into London, and reduce delays to the service for everyone.

In turn, this could open up other avenues for expansion – this line runs through a number of sites that would be excellent for New Towns, such as Crewe Hill, Bayford and Watton-in-Stone, as well as many areas ripe for greenfield and brownfield development. New passing loops, or a relocated depot, might allow even higher frequencies. In the long term, we could extend the line seven kilometres to Hitchin, or even further to Cambridge, and an underground expansion to Waterloo. But first we need to get the basic connection between Moorgate and Stevenage to operate as smoothly as it does between Tsukuba and Akihabara.

Bring on the “the Hertfordshire Express”!